First organic mango butter worldwide

Although mango butter is an important raw material for cosmetics manufacturers, it has never been available in organic quality. That is, until Dr. Hauschka set the wheels in motion for a raw materials project in India. Both the project and the raw material passed the testing stage, meaning that Dr. Hauschka will now use only organic mango butter for its products. Sourcing this valuable raw material in organic quality comes at a price: Dr. Hauschka pays 10 times the world market price for conventional mango butter, i.e. between €120 and €150 per kilogram.

Additional Information

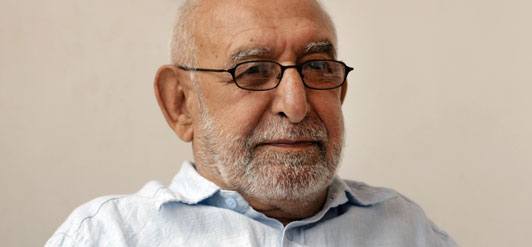

Christine Ellinger – a raw materials purchaser at WALA Heilmittel GmbH, which produces Dr. Hauschka Skin Care products – is the driving force behind organic mango butter. WALA’s aim is to expand organic farming worldwide, i.e. farming without pesticides or artificial fertilisers. As Christine Ellinger says: “Organic farming benefits both people and their natural surroundings.” She found it hard to believe that, although mangoes were already being grown in ecologically certified quality, the fruit’s valuable stones were not being put to good use. As she explains: “Some of the organic mangoes on the market are sold as fresh fruit, but most of it reaches consumers in the form of juice or dried fruit.” This leaves the skin and the stone – and the stone is the very part of the fruit that interests Christine Ellinger, as the stones within contain valuable raw materials for cosmetics.

Organic mango butter – a processing project

Mangoes grow in many different parts of the world. Christine Ellinger travelled around different continents meeting potential business partners until she found the right one in 2008: Nanalal Satra, Managing Director of the Castor Products Company in India, which has already been producing organic cold-pressed castor oil for WALA for several years. “Nanalal Satra understood immediately what we needed”, says Christine Ellinger. In spite of this, it took some time to clear up the many questions associated with organic mango butter production. Christine Ellinger’s project was leading her into uncharted territory and there were many questions to be answered. For instance, how to extract the mango seeds from the mango stone. Or how to extract the mango butter from the seeds. Or how to ensure that the mango butter remains stable without using artificial preservatives? As Christine Ellinger reports: “In the beginning, we didn’t know what quantity of fruit was necessary to produce the amount of organic mango butter we required.” With a view to finding this out, the first processing attempts took place in 2009.

In order to obtain the mango butter, the stones first need to be dried in the sun for a number of days. Following this, the stones can be cut open by hand and the seeds removed for further drying. Quite a challenge, given that the rainy season begins shortly after the mango harvest. Because of this, it is usually necessary to dry some of the seats completely in ovens. In order to minimise the amount of non-renewable energy used, Nanalal Satra and WALA looked to solar energy. “We commissioned a study to ascertain the best way to dry seeds using solar energy”, says Christine Ellinger. As soon as all of the seeds are dry, they are sent by ship to Germany, where the valuable organic mango butter is extracted from them. WALA’s aim is to source the mango butter directly from India, so that a greater part of the value-adding process remains in the country. And even at this early stage, significant value has been added, given that the stones are no longer discarded or burnt, but are processed instead. The benefit for Nanalal Satra is that he can employ an extra 40 seasonal workers for the purpose of extracting the organic mango stones.

Mango butter – raw material with a melting texture

Mango butter has a similar consistency to cocoa butter. It nourishes the skin, providing it with various fatty acids and helping to keep it soft and supple. Mango butter also helps to reduce fine lines and is particularly effective at treating rough skin. It even provides light protection against UV rays. Mango butter is also edible and is used, among other things, to make chocolate.

Mango butter at Dr. Hauschka

The following Dr. Hauschka products contain organic mango butter:

- Firming Mask: smoothing, firming intensive care for dry skin that is losing tone

- Daily Hydrating Eye Cream: light, moisture-retaining and smoothing eye care that helps to prevent fine lines

- Lip Gloss

- Dr. Hauschka Med Ice Plant Face Cream: for very dry, flaky skin that is prone to itching. Daily facial moisturiser for neurodermitic skin

- Dr. Hauschka Med Intensive Ice Plant Cream – for treating areas of very dry, flaky skin that is prone to itching. Complements treatments for neurodermitic skin Dr.Hauschka Med Ice Plant Body Care Lotion – for very dry, flaky skin that is prone to itching. For daily care of neurodermitic skin

Introducing essential rose oil from Ethiopia

When it comes to sources of essential rose oil, countries such as Turkey, Bulgaria, Iran and Afghanistan come to mind – but Ethiopia? As it turns out, the Ethiopian highlands, which are known for their coffee, provide the ideal conditions for growing the very fragrant Damask rose, and this "Rosa damascena" yields an exceptionally precious essential oil.

Additional Information

Seven years ago, Ethiopian farmer Fekade Lakew joined forces with WALA Heilmittel GmbH and began cultivating Damask roses in keeping with the principles of biodynamic agriculture. This year he distilled the first batch of essential rose oil. This is the first rose oil production in sub-Saharan Africa that is transitioning to organic standards.

The rose farm Terra PLC is located in Debre Birhan, some 125 kilometres north of Ethiopia's capital city, Addis Abeba, at an altitude of 2900 metres. This high mountainous landscape is ideal for growing Damask roses. Everything began at the farm in 2002, when vegetables were planted there. After that came a brief phase of cultivating cut roses, but they did not tolerate the late frosts which can occur in the Ethiopian highlands. Fekade Lakew subsequently switched to Damask roses.

He was soon in contact with WALA, which showed great interest in his efforts. “We had long been considering an attempt at growing roses near the Equator,” said Ralf Kunert, head of raw-material purchasing at WALA. The prospects are especially promising because the closer plants grow to the Equator, the longer they blossom. In the countries known for cultivating roses such as Bulgaria, Turkey and Iran roses bloom within four weeks and have to be harvested in this time, whereas it takes eight weeks in Debre Birhan. “This is a huge advantage,” Ralf Kunert explains. “It means that we have twice the amount of time to harvest the same amount of rose blossoms.” In other words, there is less pressure on the farmers to finish the harvest quickly; fewer rose pickers are needed, and what's more, they can be often be employed beyond the season itself. Furthermore, the quality of the roses can be monitored more closely during picking, and the output of the distillation unit is more consistent. Last but not least, Ethiopian highland roses offer yet another benefit: at four grammes per blossom, they are nearly twice as heavy as the rose blossoms from other countries, which typically weigh 2 - 2.5 grammes.

WALA accepts social responsibility

WALA provided motivation for the project by donating the rose cuttings. After seven years' time, the plants had turned into hearty rose bushes. To make sure that the roses received the proper care from the very beginning and to create the best possible conditions, WALA provided Fekade Lakew and his employees a consultant in the field of biodynamic agriculture. The expert visits the rose farm at regular intervals several times a year to train and advise employees there about how to cultivate roses properly. As a means of ensuring compliance with the high standards WALA fundamentally upholds for the raw materials it processes, the first certification audit was held this year in keeping with Demeter guidelines and the fair-trade standard “fair for life.” WALA financed the costs of the audit. Recently, a distillation unit was installed as well. It was made in Ethiopia under the guidance of a Bulgarian distillery builder whom WALA had recommended. Funding came from WALA and the German aid organisation Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) , which was acting under contract with the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). “It is important to us that knowledge is generated in the country itself and amongst our project partners. Helping people to help themselves is WALA's maxim,” Ralf Kunert states.

The objective of every WALA raw-material project is to expand biological agriculture across the globe. Partners are supported on site with funding and technical expertise. WALA signs a contract to purchase the raw materials yielded by the project. This gives the project partners security in planning, and their employees can be paid their wages on a regular basis. In its supplier relations, WALA pays special attention to decent working conditions, fair wages, and conscientious and responsible use of environmental resources.

One hectare of roses for a kilogramme of essential rose oil

WALA pays Fekade Lakew and his company Terra PLC €7000 for a kilogramme of essential rose oil. Approximately one hectare of roses is needed to obtain a kilogramme of the precious oil which is used in nearly all Dr. Hauschka Skin Care products and in many WALA medicines. WALA has agreed to purchase all of the rose oil produced at the farm for a period of ten years. “After that, we want it to be no more than 60-70% of his output,” Ralf Kunert says. “We don't want a project partner to be dependent on us; instead, they need to have several customers so they can stand on their own two feet.”

In the meantime, Fekade Lakew has leased another 14 hectares of land in Angolela, some ten kilometres away. The state currently does not permit private land ownership with the exception of a very small lot for personal use. Several rose bushes grow in Angolela, and soon there will be many more if farmers in the region follow Fekade Lakew's example. This may happen rapidly, since people in a neighbouring village have expressed interest. If all goes well, they too will start growing roses and have essential rose oil produced in the new distillation unit at Terra PLC. The roses are blooming in Ethiopia, and as they do, the economic and social situation of some families there can slowly but steadily improve.

From the Cape of Good Hope: Ice plants from South Africa

The heat-resistant ice plant at the heart of Dr. Hauschka Med Skin products originates in South Africa. A visit with Ulrich Feiter, who cultivates ice plants and whose relationship with WALA dates back many years.

Additional Information

Seven o’clock on a winter morning in South Africa. The call of the ibis cuts through the silence. The sun has just risen when seven employees of the South African Parceval Ltd. Pharmaceuticals begin with the harvest of the ice plants that grow on the fields of the company’s Waterkloof Farm. It is 14 degrees Celsius on this August morning, cool in comparison to the 45 degrees often reached here in summer. Today’s harvest target is 1.5 tons; since the plants have grown lavishly, it is reached after just three hours.

Parceval Ltd. Pharmaceuticals produces around ten tons of ice plants (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum) each year on its biodynamically cultivated, certified organic Waterkloof Farm. For 14 years the farmers have worked to produce seeds and compost, cultivate young plants and harvest grown ones. They cultivate the ice plant in the winter months because it grows faster and is juicier. In the natural habitat of the ice plant, one recognises its true nature. As a pioneer plant, it likes to colonise areas whose normal ecosystem has been disturbed.

Ulrich Feiter is the founder and head of Parceval Ltd. Pharmaceuticals. His association with WALA dates back as far as 1986. At that time, the trained gardener worked for almost two years as an intern in different departments at WALA. Among other things, he received an introduction to the rhythmic manufacturing process, which is used to produce the stable, water-based plant extracts known as mother tinctures. Feiter went to South Africa armed with this knowledge and a contract with WALA to produce mother tinctures from the heat-loving bryophyllum plant.

Ulrich Feiter does not see his role in South Africa as merely that of a contract manufacturer. “It was never about the profit”, he says when asked about his vision. He has always been far more interested in passing on ideas, building bridges and helping Africa. This is why in 2005 he initiated AAMPS, the Association for African Medicinal Plants Standards, an organisation which most recently published descriptions of more than 50 African medicinal plants with the aim of promoting their use. And why he is currently doing the preliminary work for setting up an employee foundation which will give his employees a financial stake in Parceval and a voice in the company's business decisions. Building a shared sense of responsibility is a major challenge, requiring patience and many discussions. But is the right step going forward.

Organic castor oil from India

Castor oil is a moisturising component in a variety of Dr. Hauschka Skin Care products and forms the basis of Dr. Hauschka bath oils. When WALA decided to transition to certified organic castor oil, it was discovered that this raw material was not available in organic quality anywhere in the world. But this could be changed, WALA raw materials purchaser Christine Ellinger said to herself in 2005, and began activating her contacts to organic farmers in India and to Satvik, an Indian non-governmental organisation (NGO).

Additional Information

A motivated group of ecologically minded Indian farmers founded a NGO called Satvik in 1995. Its initial aim was to promote rain-fed farming, a method suited to the ecology of the arid Kutch region of northern India. After a strong earthquake killed at least 20,000 people in this district in 2001 and many survivors were struggling to maintain their livelihoods, it became all the more important to switch over to a method of farming that is less cost intensive and at the same time preserves or even improves soil fertility. Satvik’s efforts became more important than ever.

The first certified organic castor oil

When Christine Ellinger, an ecotrophologist and agricultural scientist, approached Satvik with her question about organic castor oil in 2005, she came at exactly the right time. The farmers were already following organic criteria in their production, but had not yet received official organic certification. By providing financial support for Satvik’s advisory function as well as the benefit of WALA’s many years of experience, the company was able to help obtain organic certification for the entire castor oil plant cultivation and processing chain from the Institute for Market Ecology (IMO). This independent certification body tests ecological aspects of products, agriculture, processing, import and commerce for compliance with EU organic regulations. 2005 marked the beginning of a longstanding partnership that led to the world première of certified organic castor oil.

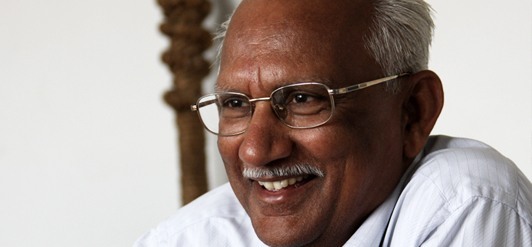

My dream is to process only organically cultivated castor beans

Nanalal Satra, owner and managing director of Castor Products Company in Nandgam in India’s Kutch district, has been in contact with WALA since 2005. Christine Ellinger’s enquiry prompted Satvik to initiate contact between WALA and Nanalal Satra. Since 2007, his oil pressing facility has been producing cold-pressed castor oil from the organically cultivated castor beans that he purchases from organically certified farms in the region – for a price that is 15 to 18 percent higher than that of conventionally grown castor beans. He was so enthusiastic about the organic production methods that in 2009 he set up another production line, certified by IMO, which is used exclusively for the production of organically certified castor oil. Nanalal Satra has used the increased revenues from the sales of organic castor oil to set up recreation rooms for his workers, to support farmers in transitioning to organic cultivation and receiving certification, and to make it possible for the farmers to cook using biogas. Fifty farmers have already received financing for biogas systems – which provide a family with one cow enough fuel to cook all their meals. In the arid, almost treeless Kutch region, this is a blessing.

Financial independence as a main goal

Today the agricultural land of a good 140 families has been organically certified. They grow around 277 tons of castor beans on approximately 1,175 hectares of land – ensuring a regular source of supplementary income. Nanalal Satra’s oil production of 60 tons per year now far exceeds the demand from WALA, allowing him to cooperate with several different trading partners. “This is in our interest as well”, says Christine Ellinger. After all, a major goal is to encourage and support industries in structurally disadvantaged areas until they become stabile and self-sustaining – and help the people of the region to achieve financial independence and improved social conditions. In addition to business advice, the NGO also runs health and education programmes. When Christine Ellinger visits, she also pays attention to the development of the community. The last time she was there, Nanalal Satra proudly showed her the improved recreational rooms for his employees. Christine Ellinger’s happiness is written on her face. Encounters between different cultures can bear a variety of fruits.

Roses from Afghanistan

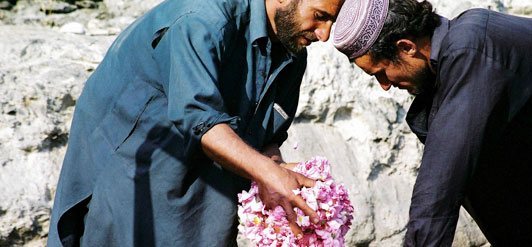

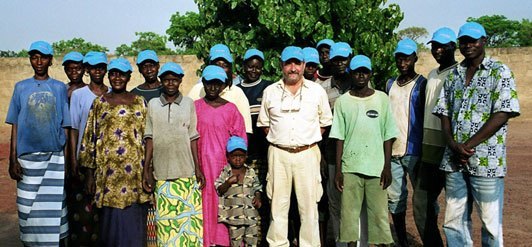

In order to combat the opium trade in the long term – 80 percent of the world's heroin supply comes from Afghanistan – it is essential to offer the people an alternative means of securing a livelihood. In October 2004, on the initiative of German Agro Action, a project for producing rose oil was therefore started in which 700 farmers are now growing Damask roses on more than 100 hectares of land. With the production of rose oil an ancient Afghan tradition was brought back to life. Today, a large volume of rose oil is produced, most of which is sold to WALA, who has supported the project since it first began.

Additional Information

WALA first expressed an interest in the Afghan rose oil in the summer of 2006 and has since been supporting the project with expertise and know how. The cooperation provides the manufacturer of natural skin care products with an additional source of the costly commodity in view of the steadily growing demand for oils from ecologically cultivated plants. The collaboration between WALA and German Agro Action was made possible by the fact that the farmers were willing to undergo certification to comply with the requirements of natural skin care.

The Scent of Roses in the Desert

There is a scent of roses in the air. Hans Supenkämper walks with Mahdi Maazolahi between the tall willow trees silhouetted against the brilliant blue sky and the building containing the distillery to the place where the compost is maturing. The 4000-metre high mountains in the distance are still covered in snow but the two men, so different from each other, are already beginning to feel the heat of this May day. The agriculturist Hans Supenkämper, a tall, sturdy man with gentle eyes, is a WALA consultant on biodynamic agriculture who advises farmers in Iran. Today he is visiting the fields of the mountain village Mehdi Abad with the agricultural adviser of the Zahra Rosewater Company, Mahdi Maazolahi, to appraise the compost started the previous autumn.

Additional Information

Pistachio Shells to Compost

Mahdi Maazolahi, a small man with thick dark hair and a round face, is never still. He moves deftly beside the tall German, who is wearing his trade-mark light brown hat with the cord. Hans Supenkämper is satisfied. The pistachio shells have completely decomposed, the resulting soil resembles fine crumbs, not too dry and not too moist and with a pleasant smell. Carefully he re-covers the compost heap with a tarpaulin to prevent too much evaporation in this desert-like region. By some kind of wonder a profusion of roses is thriving in a landscape characterized by a lack of water. Few trees and only a little greenery cover the hard ground of the lonely mountain region. An audible silence surrounds the women flower-pickers who are quietly harvesting the fresh Damascene rose blooms in the neighbouring field. They have bags slung around their hips, into which they put the flowers they have collected. When the bag is full they shake the flowers out into bigger sacks that their menfolk then carry to the distillery. With their colourful dresses and headscarves they stand out among the pinkly blossoming rose bushes.

The fields in Mehdi Abad are trial fields belonging to the Iranian firm Zahra Rosewater Company which, with WALA’s support, is working them biodynamically. Zahra gets most of its rose essential oil and rose water from the Lalehzar valley which lies in the centre of Iran at about 2200 metres above sea-level. The 83-year-old founder of Zahra Rosewater, Homayoun Sanati, loves to tell how he and his wife were surprised by the intensive taste of the mint when they went for a meal in the Lalehzar valley. It seemed an obvious idea to cultivate roses on the land inherited from his father Abdul-Hossein Sanati. Today 1500 farmers collaborate with the Zahra Rosewater Company, 50 percent of which belongs to the Sanati Foundation, an institution founded by Homayoun Sanati’s grandfather.

Tracking Down Europe’s Secret

Haj Ali Akbar Sanati (1858–1938), a knowledge-hungry trader from the Iranian desert town of Kerman, was looking for an answer to the question of what made Europe so successful. Around 1901 he set off on foot to find it. His path led him via India and the Ottoman Empire to Vienna. He was gone for ten years before returning to Kerman by way of Russia and Central Asia. With him he brought the answer to his quest: education and industry were the secret he had been searching for. So in his home town Kerman, until then a quiet backwater, he founded a textile industry as well as an orphanage that gave children not only shelter but also an upbringing and instruction, including instruction in industrial work. He took for himself the name Sanati, which is Persian Farsi and means ‘industrial’. At that time family names were unknown in Iran. Many of the orphans chose to take the name Sanati, however. In the early 1960s Homayoun Sanati’s father established a museum of modern art and a library on the site of the orphanage. They are still there today.

Children Are Our Future

"We must teach the children to think, not just the rote learning taught in state schools.“ Homayoun Sanati’s eyes are fiery when he speaks of his latest project. In 1974, after the death of his father, he took over the management of the orphanage, among other things. Since taking on Ali Mostafavi, a professor of chemistry, as general manager of Zahra Rosewater in 2006 he devotes more time to the orphanages of the Sanati Foundation. In addition to the boys’ orphanage in Kerman there is one for girls in Bam, a town severely damaged by a violent earthquake; a kindergarten for disabled children in Kerman and a home for mentally retarded girls, who are often the targets of violence or abuse in the family. A total of 200 children find shelter and protection in the Foundation’s institutions. For Homayoun Sanati children represent the future of Iran. „We must educate the mothers“, he adds in a determined voice. For it is they who equip the children with a knowledge of ethics and social conduct to accompany them on their path through life.

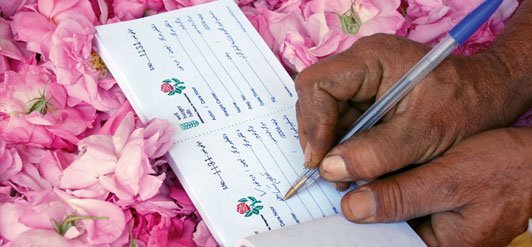

Rose Months

Around the distillery in Lalehzar it is busy as a hive of bees in the months of May and June. On mopeds, donkeys, lorries and tractors or even on foot the farmers of the surrounding areas hurry to deliver their freshly harvested roses. At the entrance to the warehouse, where the air is pregnant with the scent of the roses spread on the ground, a distillery employee sits beside a large set of scales. He weighs every sackful of roses precisely, enters the weight in a receipt book and gives the farmer a receipt which he can take to be paid directly afterwards. "The price we pay is good, and we want the farmers to know that”, says Ali Mostafavi, general manager of Zahra Rosewater. At the end of the year Zahra also pays bonuses to their contract growers if the turnover is high enough. "Of course we also have to invest in the business“, says Mostafavi with his gentle smile. For example, a new bottling line is needed for the approximately 20 different plant distillates, from peppermint water and willow water to the forty-herb water, that Zahra produces in addition to its essential oils, herbal salts and fruit teas. With this broad range of products Zahra can continue to utilise the distillery once the short rose season has finished.

Rose Oil and Rose Water

In the rose delivery hall everything happens very quickly. In the background employees take charge of the sacks and empty the roses on to the clean floor of the hall. The flowers must not be allowed to get hot, otherwise they would lose too much of the costly rose essential oil. For this reason harvesting starts early in the morning and everyone in the Lalehzar valley who is not aged or infirm is roped in to help. Again and again the distillery workers turn the roses over to ensure that they remain cool. When stills in the neighbouring hall become free the flowers are hastily taken over and wrapped in blue tarpaulins to be heaved up into the upper vessel of the distilling apparatus. The vessels can hold 500 kilograms of rose flowers which boil for three hours with around 500 litres of water. Zahra Rosewater processes more than 900 tons of rose flowers each year. This work yields a precious 900 tons of rose water and about 150 litres of rose flower oil which are constantly analysed for quality in their own laboratory. "Our aim is to increase the yield to 1100 tons of rose flowers per year,” says Ali Mostafavi. The long-term contract of cooperation with WALA to purchase more than a third of the rose oil produced as well as dried rose blossoms makes him optimistic. New fields in Shiraz and Dharab will contribute to this growth. Mostafavi is pleased with the good business relations with WALA. In January 2008 he paid a visit to the German company to discuss a joint quality standard, among other things.

Education and Training

The 1500 farmers who work for Zahra Rosewater are independent entrepreneurs. In contracts concluded with Zahra they undertake not to use chemical fertilisers now that Zahra has the fields certified as organic by the British Soil Association. "It is a challenge to stop the farmers treating the roses with chemical agents,” says Mostafavi, “because the Iranian government subsidises chemical fertilizers and initially these are the only ones the farmers are familiar with.” Education and training, for example by WALA’s agriculturist Hans Supenkämper, who works following biodynamic principles, are therefore important pillars of the collaboration with these farmers. Apart from this, Zahra provides the farmers not only with rose cuttings but also with free natural fertilisers from compost. Anyone violating the prohibition on chemical fertilisers is excluded from the contract for four years. "But we don’t leave the farmers on their own in this situation,” Hamayoun Sanati tells us. His vision is to convert the whole Lalehzar valley to organic agriculture, from dairy cows and roses to fruit and vegetables. If a farmer did use chemical fertilizers he would be reported, but Zahra would still take his roses – albeit at a lower price – and would have them distilled in conventional distilleries. Anyone working with Zahra is family. This attitude is reinforced by a regular newspaper for the farmers in Lalehzar supervised by Mahdi Maazolahi. It reports on events covering all aspects of roses and rose-growing, publishes portraits of individual farmers, announces festivals and news from the villages and includes special pages for the women and children. As part of this family-oriented collaboration, families in need are granted an advance on their income, older people no longer able to work receive a kind of pension and legal aid is provided in cases of dispute. Zahra has improved the water supply to the villages and supports the schools. A local health centre set up by Zahra guarantees primary health care. Anyone needing to visit a specialist in Kerman is helped with transport. Anyone wishing to marry is given a credit at the very low rate of interest of 4 percent instead of the 14 percent charged by the Iranian banks. Zahra makes it possible for specially gifted children to attend school in Kerman. The hope is that they will return to their villages with a good education and work there. The idea is working: Lalehzar has the lowest unemployment rate in the whole region. Migration from the countryside to the towns – widespread elsewhere in Iran because middlemen mean that agriculture is scarcely financially viable any longer – is nearly unknown here. Even the Iranian Ministry of Agriculture views the enterprise benevolently and offered Zahra credit to continue expanding. However, this was not necessary because Zahra is well able to finance itself and can even donate part of its profits to the orphanages of the Sanati Foundation.

"We are planting wheat in trial fields with and without chemical fertilisers and then comparing both yield and costs,” says Ali Mostafavi. He passes the results on to the farmers, who are capable of deciding for themselves whether organic farming is a viable option. It is hoped that the farmers will develop a feeling for organic farming and pursue it out of their own conviction. Even if in Iran itself there is no market for organic products as yet, except for occasional pockets in Teheran, Zahra Rosewater believes in its organic Velvet Revolution.

The Beginnings

The cooing of the doves fills the inner courtyard of the ochre-coloured brick building constructed by grandfather Sanati in Kerman. Today it houses the headquarters of the Zahra Rosewater Company and is home to Homayoun Sanati. Its walls keep out the hubbub of Kerman, now a city of a million people, and it is a good place to ponder on the origins of Zahra.

After Homayoun Sanati and his wife decided to cultivate roses in Lalehzar they acquired Damask rose cuttings from the traditional Iranian rose-growing region Kashan in the province of Isfahan. The first trials were overwhelming. After just eighteen months the bushy rose trees were yielding blooms with a 50 percent higher oil content than roses from Kashan. This led the Sanatis to plant a 20-hectare rose field, although the farmers of the region were very suspicious of this new cultivation. Then the Iranian revolution happened. When Khomeini came to power Homayoun Sanati was arrested. He was accused of being a CIA agent because he worked for the American publishing company Franklin. Actually, his only job there was to translate English-language fiction and text books and publish them in the Iranian language Farsi. But the mere fact that he had published 1500 books was regarded as a crime against Islam, because he was said to have subverted the culture of Islam by publicising American ideas. After eight months in solitary confinement in a damp cell with no light he was forced to spend a further five years in prison. He was released in 1983. In the meantime his wife was left alone to look after the roses, which were like children to her. So it was even more terrible for her to have to look on as the farmers in Lalehzar stopped watering the young plants every 14 days and watered them just once over the whole summer. But then a miracle happened. The roses continued to grow, be green and bloom abundantly. The farmers were so impressed that from then on they began to believe in growing roses: they could see that with little work and a minimum of water they produced a far better harvest than wheat or potatoes or even the opium poppies which they had long been growing illegally to stretch their meagre income. "So my time in prison did have one positive outcome“, grins Homayoun Sanati with boyish charm. Following his grandfather’s advice: "Never be afraid of fear", he was able to survive his time in prison. During his time in solitary confinement he even composed hundreds of verses about the rose, all of which he kept in his head and only wrote down after his liberation. "Our difficulties are our greatest treasures“, he concludes.

Further information:

Shea Butter from Burkina Faso

The shea butter for Dr. Hauschka Skin Care comes from Burkino Faso. In 2001, we provided the stimulus for an organically certified project in the region around Diarabakoko in the south-west of the country. 2,200 women from 17 villages are today involved in the project and collect the shea nuts from several protected, organically certified collection areas.

Additional Information

Women´s gold: Shea butter

The collectors in the project village of Diarabakoko independently organise themselves in a producer association. This is a women-only association, as is common and natural in Africa. Shea butter has always been a women’s thing and only they are authorised to harvest the nuts. The women named their association ‘IKEUFA’ (Faire bien et meilleur de Diarabakoko), which can be roughly translated as: Do good and better things in Diarabakoko. Their earnings from the shea nut sales enable them to pay for their children’s school fees – so that all of them, rather than just the lucky few can go to school. They are also able to pay for basic essentials like food and medicines.

Process within the country

After harvesting the nuts within the scope of the project, the women shell, dry and place them into interim storage in warehouses that are co-financed by WALA. The nearby organically certified company Agrifaso, with its head office in Bobo-Dioulasso, purchases the nuts and uses transporters to move them straight from the villages to its small processing unit. There, the shelled nuts are pressed under warm conditions and turned into shea butter. Agrifaso has 40 permanent employees, who ensure the continual production of the shea butter in consistently good quality. Finally, the raw shea butter is subjected to an organically certified refining process to reduce its highly characteristic natural odour.